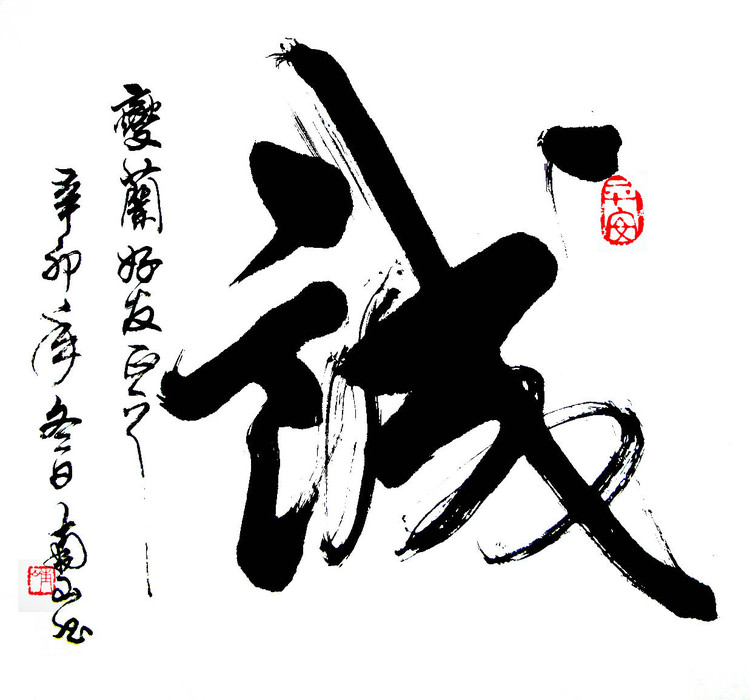

True Samurai ranged from the most brutish to the most noble of individuals but the warrior without falsehood (hence the makoto calligraphy) always has a choice to express benevolence even in the most dire of circumstances. That choice is central to the practice of Aikido.

O’sensei said that “the challenge is not to create peace in others but to manifest peace in the face of our own aggression.” This statement grows out of the samurai tenet titled here that refers to reflecting the capacity to show mercy even in the expression of lethal justice. In the case of the samurai the examples I have come across include returning your adversary their sword when dropped so that your victory an their death maintain honor, that when a samurai is the clear superior they would allow the other to take their own life rather then be defeated, and when executing someone that the sword cut would stop just short of fully separating the head from the body to preserve the “whole person.”

The powerful mythos surrounding the concept of “bushi no nasake” should be starting point of aikido rather than an ideal. Aikido practice should not limited to a nice metaphor for life that changes to violence in real application, it should be a practice of action as it will be performed facing the real “threats” of our day to day life as well as for the unlikely need to defend ourselves against physical violence. Aikido is a “budo” which means it has to stand up and be effective against real violence but aikido techniques by design have already chosen to forgo violence and harm as the solution, our challenge is to not put our aggression back into the technique in desperation to be “successful.” Relying on inflicting pain in the application of a technique or executing an atemi as a striking blow may be really effective and justifiable but it ceases to be aikido and falls short of both Makoto and Nasake.